Anna Hoetjes (AH) in conversation with curator Caroline Elgh Klingborg (CEK)

CEK: In your two channel video installation you are depicting a world where women and not men conquered space. The work relates as much to science history as to science fiction, but also feminism. What is the potential of science fiction for you as an artist?

AH: Like many people, I prefer the term speculative fiction to science fiction. More than a medium to describe scientific development, I see it as a medium where both the past and the future can be creatively (re)interpreted. For a few years I worked in the Netherlands film archive (EYE), which greatly inspired Eyes in the Sky. There’s one example from early cinema that I particularly like to quote – I never actually saw it, I only ever had it described to me. This film from the early 20th century shows a woman buying her clothes from a screen: online shopping predicted more than 100 years ago! But in the film the woman’s shopping cart is sent to her husband, who makes the payment. Technical developments are often easier to imagine than social developments. The idea that a woman could pay for her own clothes was apparently harder to imagine than the technical possibility of online shopping.

Our understanding of the past and the future is a complex web of cultural subjectivity, power structures and commercial/political interests. I think the artistic potential of speculative fiction is to jump into this web and weave some unexpected, unadapted parts into it. To challenge a contemporary social reality, to challenge the past that led us to this contemporary reality and to question the future that is set out for us. For me this means questioning the invisibility of women, in Eyes in the Sky particularly within the history of space science.

CEK: The narrator in your film is Varvara Tsiolkovskij who was married to the Russian scientist Konstantin Tsiolkovskij. He created the first realistic ideas about how humans could travel into space. Who is Varvara – who has got her eyes in the sky – in your piece?

AH: I did a lot of research into early space science and encountered many inspiring men. Only after a while did I start wondering how many inspiring women I could’ve encountered if the social constructs of the time had been different.

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was an interesting figure. He had a hearing disability and lived in the remote countryside in Russia in the late 19th century. His interest in space travel developed while reading Jules Verne as a socially isolated child. He later studied to be a physicist in Moscow. While developing his theories he made striking drawings of his calculations and visions of how people could travel into space. His theories didn’t find a huge audience during his lifetime, but he did become part of the Kosmist movement, a group of theologists, scientists and artists who had an unstoppable faith in science and technology, believing it would lead to immortal existence in infinite (outer) space. The authorities rather ridiculed them at the time. Much later, during the space race in the Cold War, the Soviet Union put Tsiolkovsky forward as ‘the earliest’ space pioneer in competition with German and American early space pioneers, like Hermann Oberth and Robert Goddard. Tsiolkovky’s historical persona is very much a political and ideological construct.

Varvara was his wife. Hardly any information can be found on her. My interest wasn’t so much to reconstruct her real life, but rather to create a fictional life for her. To introduce her as an authority, an eye witness, an explorer, adventurer and pioneer. To let her act out the hypothetical theories of her husband, who no doubt relied on his wife’s labour in some way or another while creating his visions. People who see Eyes in the Sky often assume that Varvara’s narrative is based on existing diaries or interviews, no matter how far fetched, fictional and body-horrific her experiences in my piece are.

CEK: A question that you seem to ask in your film is how the utopian and dystopian scenarios from the past influence how we look at ourselves and technology today. Is that correct reading of your work?

There are parallels between the early 20th century and now, in the sense that in the last 20 years we have experienced a radical change in the structure of labour, capitalism, communication and navigation. I keep finding myself drawn back to the early 20th century and lately especially the speculative fiction from that period. This period is dominated by white men. The women and people of color who were active as supporters or collaborators of these men are often rendered invisible. The more I was researching, the more that started to bother me. The late 19th and early 20th century have formed the political, social, industrial and economic structures we still experience today. So, in order to render certain perspectives visible, some time traveling has to be done. I believe it’s interesting and fun to return to this forming era and insert some facts and fiction into history.

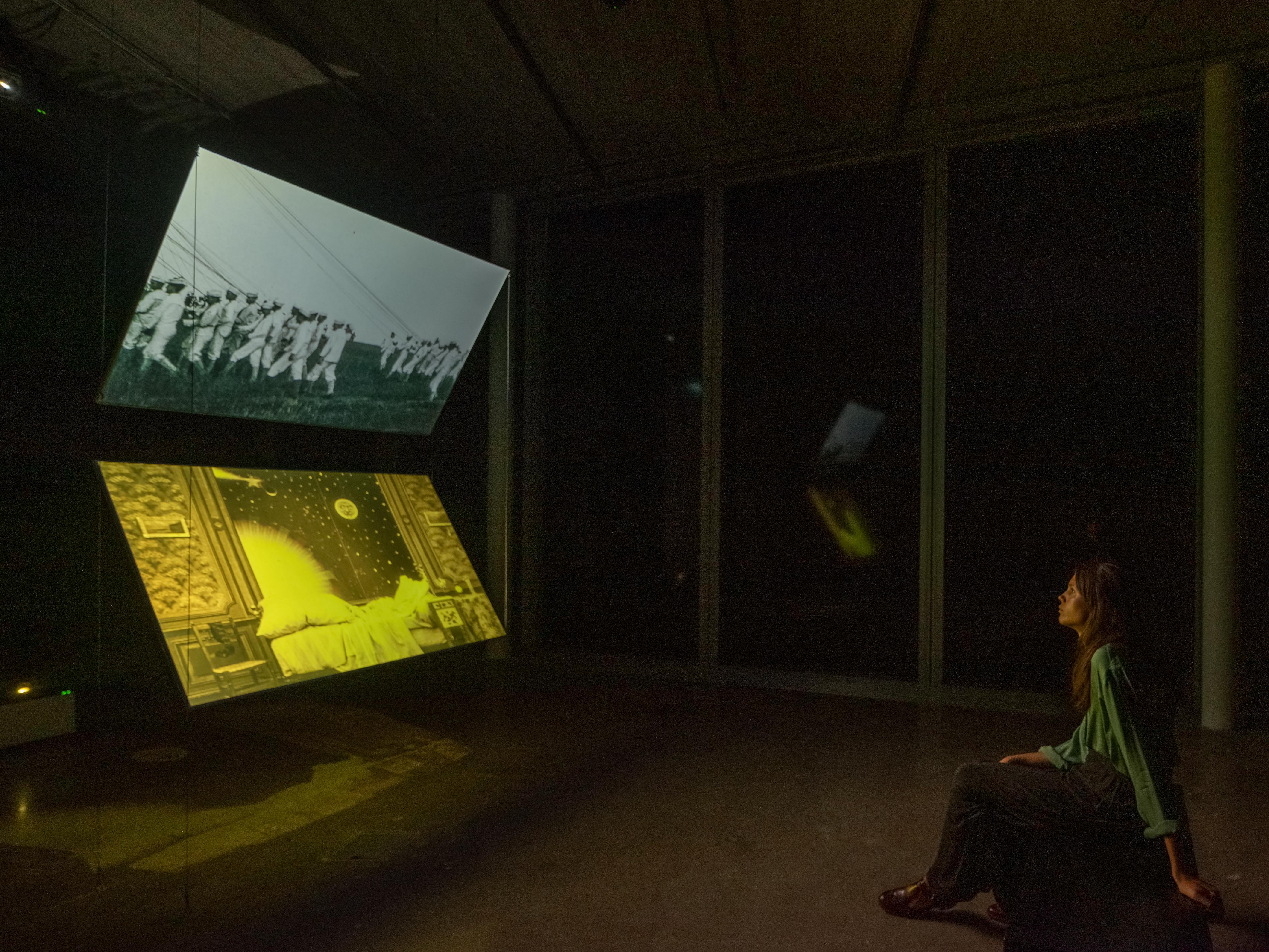

Top picture: Anna Hoetjes, Eyes in the Sky, 2018. Still from video installation. Source material ESTEC, European Space Agency.