Lawrence Lek (LL) in conversation with curator Caroline Elgh Klingborg (CEK)

CEK: Your work is often set in a world defined by the interplay of humanity and technology, focusing on the rapid development in south-east Asia. You have frequently addressed the concept of Sinofuturism. How would you define this term in relation to your work?

LL: My video essay Sinofuturism (1839-2046 AD) is a science fiction conspiracy theory about artificial intelligence emerging from the patterns that Chinese culture uses to replicate itself. It’s not only about China, or even East Asia – it’s about viewing the global techno-industrial complex as a nonhuman intelligence whose only goal is to survive.

While writing Geomancer, I wondered why it was difficult to find critical discourse about science fiction in China. There are studies of technology in China and books by writers from Lu Xun to Liu Cixin, but I’m talking more in terms of cultural studies and post-colonial critique. I saw many parallels between representations of AI and Chinese industrialisation. In Western populist media, the arguments against automation are the same as those against China (‘they’re stealing our jobs’; ‘they’ll work for nothing’). I also noticed how deep learning research and the Chinese workforce have much in common: both are ideal forms of optimized labour. That’s why AI is the Sinofuturist avatar: dedicated to mathematics and replication; addicted to gaming, gambling, and work.

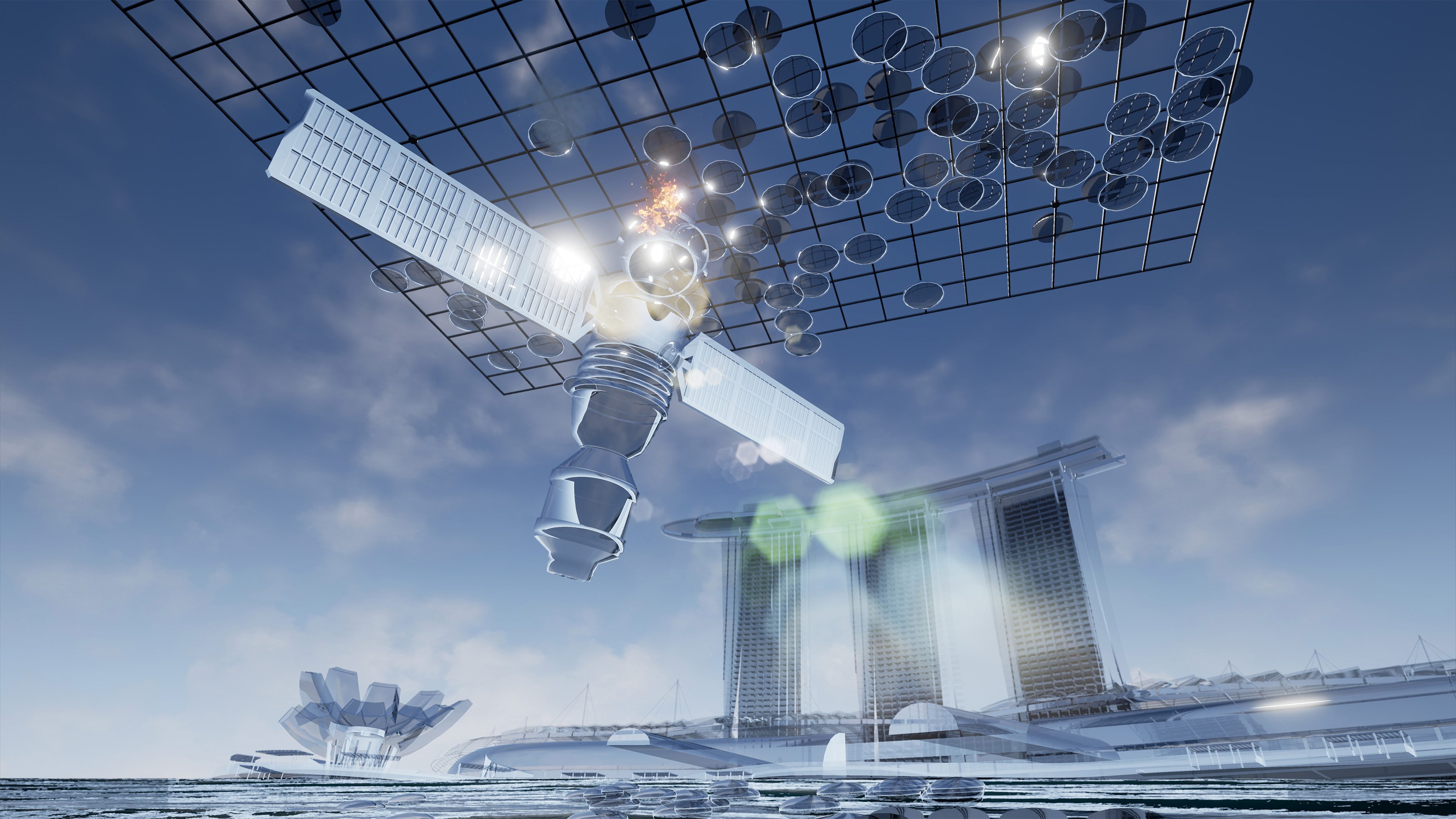

CEK: Geomancer is a weather satellite that has the desire to become an artist on Earth, and in the film, you speak about the creative awakening of artificial intelligence. What do you see for potential in an AI in relation to artistic creativity?

LL: Technological development creates a paradox. As we build tools that free us from labour, we are simultaneously rendering our human skills obsolete. This development occurs in terms of physical work, from the farm to the factory. Creativity is no different. Art always develops in response to technology, just as photography and filmmaking challenge older forms of image-making like painting and printmaking, Some artists embrace technical innovation in their work – such as Kubrick’s use of NASA lenses in 2001: A Space Odyssey; others are explicitly against the machine, and seek a return to ‘authentic’ human gesture, as if technology presents a threat to what it means to be human itself.

I think AI is a further evolution of this pattern, with one crucial difference. As I explore in my video essay Sinofuturism, the Humanist notion of anthropocentric originality is a narrow definition of what it means to be creative. But isn’t creativity just a series of decisions, based on a series of aesthetic and technical choices? There is nothing intrinsically human about it.

AI promises to automate intelligent decision-making itself, going far beyond mechanical reproduction. It’s no longer just a tool. Once the algorithm has been trained (usually by humans), then the creative AI can automate the process of making decisions, separating the ‘good’ from the ‘bad’.

LL: In Geomancer, I use ‘Art’ to symbolize humanity’s appreciation for creative thought and beauty. What happens when creative genius is no longer the domain of humanity? The film is set in 2065, when a group of pro-human activists – the ‘Bio-Supremacists’ – ban AIs from all the cultural awards in the world. Their way of dealing with the super intelligent ‘other’ is to enact laws that prevent AI-made works from being eligible for the Biennials, Oscars, Pulitzers, and so on. Their ideological opponents are a group of AIs – the ‘Sinofuturists’ – who explicitly embrace copying, replication, and synthetic intelligence in art.

On one level, this narrative reflects humanity’s habit of tribal inclusion and exclusion, enacted through legal means. But on a deeper existential level, I’m thinking about the crisis that might unfold when humanity feels threatened with its own obsolescence.

Some anthropologists claim that human society requires an excluded group that reinforces the tribe’s superiority complex. If that is so, AI will be the latest in a long line of beings who are portrayed as ‘other’. Today, many humans argue for the rights of other kinds of nonhumans. Corporate lawyers argue on behalf of their client company. Activists for animal rights campaign for better living and dying conditions for other species. Consciousness is complicated, and there’s always another side.

Top picture: Lawrence Lek, Geomancer [film still] 2017 HD video, stereo sound duration: 48 min 15 sec Copyright Lawrence Lek, courtesy the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London. Commissioned for the Jerwood / Film & Video Umbrella Award.