CHILDHOOD

A grid of twelve black-and-white images form a monumental unit in Orupabo’s work Cloud of Confusion (2024). The images are close-ups of mostly dark skinned bodies, naked dark skin and an open wound, alongside a fearful Disney animated pig, fur enveloping a groin, a ceramic four-legged animal and a gritty reproduction of the words “Dirty dirt” scrawled on a white hoodie.[1] Other motifs are more indefinable because, although the work is not a collage, Orupabo has cropped the images in a way that makes several of them difficult to decode. Some appear downright abstract. As is usual in Orupabo’s practice, the original images she has dissected are not revealed. But unlike in her collages, the excerpted images are not shaped into a new body. Rather it is up to the viewer to make the connections between the disparate images, to work through the de-formation.

For us, this work sets in motion a number of dis- and counteridentifications and interpretations as the “historical self” erupts into the here and now.[2] That part of our subjectivity, which is conveniently hidden away but emerges when a certain event, encounter, or exchange reminds us that some people can trace their ancestral origins back to the enslaved and/or colonized, while others only trace them back to the colonial and slaveholding powers. Some of us can trace our ancestry in both directions.

As mixed-black women who have grown up with Nordic culture, Cloud of Confusion put us into painful contact with inherited colonial language and imagery. The work reminds us of a Danish children’s song that continues to live a quietly disturbing life in De små synger (1948), one of the most canonized Danish children’s books, including its latest reprinting in 2018. “Inger Goes to School” (1947) is about the “vain” girl Inger, who “naughtily” wears her lavender blue Sunday dress to school.[3] In the fourth verse, she suffers the consequences:

Four boys are playing/ fighting with a n****./ Inger takes a sideways view,/ looks at the lavender blue.// See how they throw dirt about! Alas, a mighty splash/ through the air does spew,/ hitting the lavender blue.[4]

It is still unclear to us what “playing/ fighting with a n****” really means, whether this is a real person of African descent, or are we dealing with a “game” where someone has to be the n**** (as in everyone against the n****) or whether it is because the person is a n**** that they have to be covered in mud, and whether this ultimately helps to confirm their position as n****? But the moral of the song is unmistakable: Inger gets dirty just like the n**** is “dirty,” and her shameful behavior manifests itself externally, through the mud on her dress, because like the n**** she is “justly” punished.

Orupabo’s grid of images opens up a festering historical wound that is still open in the Nordic colonial reality, where blackness continues to be met with equal parts fascination and fear. Black people appear in Danish-Norwegian art and cultural history as foils, as representations of the sides of white subjects they wish to disavow. Black people are tropes, as Morrison describes, through which white subjects understand themselves in the disruption of cultural norms and transgression of taboos. The shameful, aggressive, sexual, the “dirty dirt”.

As for Orupabo, who began her practice by cutting up her own family albums and reassembling them, one gets the feeling that Cloud of Confusion also recalls or re-enacts the child’s exploration of the world, making meaning out of the images and words she encounters and seeking to understand their causality. This feeling is reinforced through the comic book reference, which, like “Inger goes to school”, traces the presence of racial violence in the child’s world.

Critical race studies scholar Ahrong Yang’s research on children’s racialized becoming in race-evasive Nordic culture notes how ideas about child innocence and white innocence coalesce.[5] “[T]he value of a child’s innocence depends on their capacity to be protected, which does not benefit children equally,” Yang writes. While innocence sticks to white Nordic bodies, it is still rarely extended to black Nordic subjects, including black mothers and children who instead become figures of culpability in the national imagination.[6] Within this logic, the black child’s innocence will always already be compromised. If anti-black racism is something about which children are expected not to know anything, black children fail to live up to this standard of childhood.

How do black children make sense of the meaningless logic of racism, forced to see and understand themselves through a white gaze? Cloud of Confusion activates and mirrors a disturbing black experience, but it also remains an unfinished puzzle. A collection of pieces that cannot be put together. Recalling Frantz Fanon in Black Skin, White Masks: “The black man is a toy in the hands of the white man. So in order to break the vicious circle, he explodes.”[7] In this way, the artist’s de-formations can be experienced as the incomprehensible, the madness and lack of coherence that determines black existence. How can we create meaning out of the fragments left to us by the colonial powers?

In Orupabo’s collages we encounter portrayals of black women resembling paper dolls held together by metal rivets, playthings. The visible de- and recontextualization gives the doll-like portrayals the character of a patchwork, assembling different skin tones and proportions of the body parts. In some places, extra body parts and various objects from the original photographs have crept in. As curator Awa Konaté notes, “the metal pins,” in Orupabo’s collages, “suggest instability, motion and transformation,” but the doll motif is also reminiscent of the role-playing games of young children with their dolls, which contribute to their development of empathy and care.[8]

Toni Morrison’s novel The Bluest Eye, set in a small town in 1940s America, explores the impact of racism on love, desire, beauty, hatred and self-hatred. In the novel, we get a glimpse into the secret treasured ritual of the narrator, a little black girl: taking apart the blonde, white blue-eyed dolls that the adults give her for Christmas. The white doll, the adults assume, is her greatest desire, however she reveals to the reader: “I had only one desire: to dismember it. To see of what it was made, to discover the dearness, to find the beauty, the desirability that had escaped me.”[9] Something analogous is at play in Orupabo’s dissections, as she works her way through anti-black visual material, processing archival images seeking to understand love and beauty, how to give care where there has been none. In Orupabo’s case, body parts are cut out of the original images, leaving the unsettling places they were found behind. The disorientation of the cropped images combined with the women’s confrontative gazes leaves us with the impression that we as viewers are encountering icons that transcend time and space, even if just for a moment.

Sources:

1. The image is a detail from Deborah Luster’s photo series One Big Self (1998-2002).

2. Claudia Rankine, Citizen: An American Lyric, Minneapolis: Greywolf Press, 2014.

3. See also Mai Takawira, “Under the White Gaze,” in This is Not Africa, exh. cat., Aarhus: ARoS, 2021.

4. Hulda Lükten, ed., De små synger, Copenhagen: Høst & Søns Forlag, 1948. p. 92. Our censorship.

5. Ahrong Yang, “Racism suitable for children? Intersections between child innocence and white innocence,” Children & Society 38, no. 4 (2024), https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12797.

6. Jan Therese Mendes, “Disciplining the disobedient Black maternal subject: the assimilatory pedagogies of public suffering and punishment,” Feminist Theory (2024), https://doi.org/10.1177/14647001231223099.

7. Frantz Fanon, Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles L. Markmann, New York: Grove Press, 2008.

8. Awa Konaté, “Frida Orupabo,” in Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2023, London: The Photographers’ Gallery, 2023.

9. Toni Morrison, The Bluest Eye, New York: Penguin Random House, 1970.

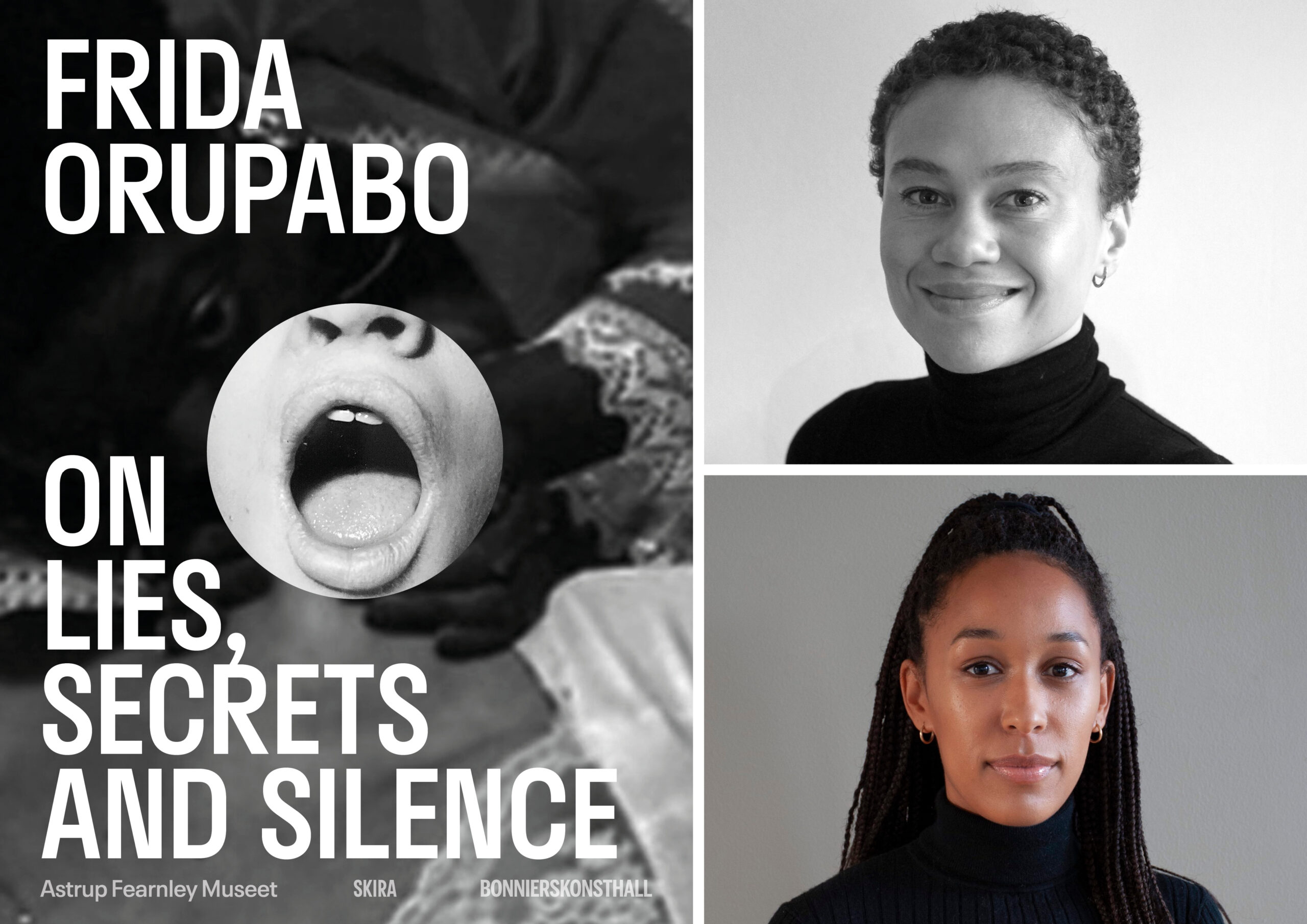

Frida Orupabo: On Lies, Secrets and Silence

The richly illustrated catalogue Frida Orupabo: On Lies, Secrets and Silence offers critically and creative texts in response to the exhibition. It begins with an introduction by Yuvinka Medina (Senior Curator at Bonniers Konsthall) and Owen Martin (Curator at Astrup Fearnley Museum), who highlight the significance of the artist’s early digital work and its relation to On Lies, Secrets and Silence. The catalogue also features original essays by Nina Cramer (PhD candidate at the University of Copenhagen, Department of Arts and Cultural Studies) and Mai Takawira (freelance curator and researcher), who explores the position of Orupabo’s work within a Nordic context, as well as by Dr. Portia Malatjie (curator and lecturer in Visual Cultures at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, University of Cape Town), who considers the connections between race, discomfort and play. Additionally, C. LeClaire (poet and author) and Hilton Als (award-winning journalist, critic and curator) contribute creative, deeply personal texts that open up for singular readings of the exhibition. The design is by Gabrielle Guy. The catalogue is published in collaboration with Astrup Fearnley Museum and Skira Editore. It will also be published in a German edition in collaboration with Sprengel Museum Hannover and Stiftung Niedersachsen, coinciding with Frida Orupabo receiving the prestigious Spectrum International Prize for Photography in 2025. The book launch is scheduled for late October 2024 at Bonniers Konsthall.

Image: Frida Orupabo, Cloud of Confusion, 2024. Photo: Jean-Baptiste Béranger, Bonniers Konsthall